Winches are the power behind the sails. A dinghy can use a 2:1 tackle to sheet in the jib, but greater purchase than that isn’t practical when tacking. Multipart tackles can work on the mainsheet, up to 8:1, but for sheets longer than 30 feet they become impractically complex and hard to release in light and heavy winds.

Mainsails on a cruising boat become too heavy to properly tension by hand. A downhaul helps tension the luff, but this tension is concentrated mostly along the bottom third.

The solution in all of these cases is powerfully-geared winches. However, grinding and tailing a basic winch requires two hands, and can require two people in any sort of breeze. A self-tailing winch makes grinding a one-person job, but the self-tailer can slip. Recently, we’ve received several questions about slipping winches, clutches, and jam cleats. Our F-24 test boat had some winch-slip problems that we eventually solved. Let’s talk it through.

SOLUTIONS

Every boat is different, but having faced and ultimately corrected a variety of winch-related deficiencies on our test boats, we’ve narrowed down the causes of the most common problems and come up with some inexpensive, practical remedies.

Technique. Most winch-slip problems can be solved through adjustments in installation and use. The lead angle is critical. If the lead angle is too low, the line’s friction over the drum skirt results in hard cranking and reduced holding power. If the lead is too high, then you’re likely to have overrides—when the line wraps over itself on the drum. Mechanically, each winch is designed to take load optimally from one direction, though it should be strong in all directions. Most winch manuals will help illustrate the ideal orientation toward the line.

The number of wraps matter. If you make too few wraps, the winch will slip, but if you add too many wraps the wraps can bind. This will increase friction and if the lead angle is also too high, there’s a good chance of an override. In the case of our F-24, an obstruction made the lead on a reacher sheet too high. We simply removed the obstruction. In another case, a barber hauler line was coming from an elevated angle; we installed a floating fairlead to correct the angle.

The stripper of a self-tailing winch should face in the direction you want the rope to pile. Typically, this means the stripper is oriented at a 25-30 degree angle in relation to a fore-aft line drawn through the middle of the winch base. Positioned this way, the winch spills each sheet directly into the cockpit. This orientation also makes it easy for crew to get a good grip on the line, and ensures a full wrap in the jaws of the self-tailer, which helps seat the rope in the jaws.

If the stripper is pointed at a 90-degree angle to the boat’s centerline, directly inboard, or at a narrow angle with the boat’s centerline, it is awkward or impossible to get a full wrap and a good tug. The winch must also be installed facing the load according to the installation manual. This is separate from the stripper orientation, which can be changed after installation.

If you have 8-inch handles and are struggling to grind, try a 10-inch handle. Racers often favor shorter handles because they spin faster.

Regarding self-tailing winches, the number of turns is also critical to proper jaw function. You can get away with mistakes if the rope diameter and type are perfect and the parts are new, but as the winch ages or if the line is stiff, slippery, or the wrong size, they are less tolerant.

In light winds there must be enough tailing force to compress the springs and pull the rope into the jaws. With too many turns on the drum, the force on the tail is very light and the rope walks out of the jaws as you grind. The firmer and fatter the rope the more force this requires. Conversely, because the jaws do not provide the secure grip of a cam cleat or jammer, as the wind increases the number of turns must increase to prevent the jaws from slipping, wearing the jaws. Simply put, the tailing force must remain relatively constant over a wide range of sheet loads so that there is enough force to pull the tail into the jaws, but not so much as to make it slip through the jaws. This is done by adjusting the number of turns on the drum. Depending on winch and rope size, about 10-20 pounds tailing force (a modest but firm one-handed pull) is about right.

Oversized Rope. There should be room for five turns on the drum without crowding. If not, the rope is too fat. It is common for sailors to up-size ropes to get an easier grip, but maximum size lines on winches, blocks, and through jammers increases friction and jamming. Instead of fatter ropes, use more efficient blocks, improve alignment, add more purchase if needed, and wear better gloves. In the case of a self-tailing winch, an over-size rope will not slide deeply into the jaws and will not fit enough turns for sufficient friction. This was the case on the F-24 jib sheets; the rope would not sit deeply in the jaws. Downsizing solved the problem.

Too small a rope is possible, but in practice surprisingly rare. A polyester rope of sufficient strength will nearly always be large enough, and even Amsteel with a cover should be large enough. Consult the manual for the range in diameter. Jammers, on the other hand, are more sensitive to size.

Rope type and condition. Dirty ropes can become too stiff to wrap smoothly into the jaws. Wash them (see “What’s the Best Way to Clean Marine Rope,” PS July 2011). Dyneema ropes are slippery and require a higher friction cover—Technora is common—to grab properly on the drum and the jaws (see “Unwrapping the Amazing Capstan Equation”). Although ropes with a fuzzy finish are supposed to grip better, their advantage over ropes with a smoother finish is negligible.

Cover Your Winches. If the jaw or stripper have plastic parts, long term UV exposure will cause them to deteriorate. Many believe winches do not need to be covered, but for this one reason, we do. And they keep birds from pooping in the handle sockets in summer, and ice out in the winter.

WINCH RESURFACING

Most likely, you don’t need to resurface your winches. Racers like texture because it reduces the number of wraps, allowing for slightly faster tacking, but adding another turn will accomplish the same thing for a cruiser with less wear on the rope and smoother easing.

Stay within the recommended rope size range. Don’t oversize, the rope needs to be drawn well inside the jaws for the self-tailer to work. If you aggressively downsize using high-modulus line you may need to add a cover (see “Adding a Polyester Cover to Dyneema Single Braid,” PS December 2018). If that does not add enough bulk, consider adding a second core; a 1/8- to 3/16-inch single braid line (most often Dyneema, because it is slippery and easier to work with) can be pulled inside the core. You will need some extra length to work with, because bulking up the core will require you to bunch up the cover, shortening the rope. For guidance, there is a helpful video (www.youtube.com/watch?v=kzsvFz6a_ts).

Sanding. If you want to scuff-up an old bronze or stainless drum, take it easy. Overly aggressive sanding will make the drum into a file, and racers have reported fuzzing ropes in just a few days when re-texturing was over done. On one manually textured polymer drum we tried, the line refused to ease smoothly. Additionally, neither chrome nor anodizing sand erasily. If damaged, the chrome will peel. If you decide to scuff up your drum, start with a very fine grit (320 grit), go gently, and gradually decrease grit. A sanding sponge handles curves well (see “Hand Abrasives Round-Up,” PS July 2006).

We’ve seen resurfacing done using a center punch to drive tiny dimples into the drum. We don’t recommend this. The chrome or anodizing will be ruined and must be redone. The surface will be too harsh on lines. Finally, the impact could damage the drum.

Pneumatic scaler. We have seen some very neat work using a scaler. A $25 pneumatic needle scaler from Harbor Freight was modified by rounding the needles on a grinder. Using a scrap of wood as a guide, work your way gently around the drum. On the job we observed, the result was a profile similar to the original Harken drum without apparent damage to the anodizing. We have not tested this process ourselves, and can imagine this will only work on aluminum and non-plated drums.

Machine shop knurling. For knurling, the drum is turned on a metal lathe as a textured wheel presses a pattern into the metal. We have heard so many bad reports, including cracked plating and a rough, file-like surface, that we cannot recommend this.

Harken used to retexture drums, but the business was small and labor intensive. Now they service only select, very high-end winches, and suggest either getting a machine shop to put on a light knurl on the drum (which sometimes leads to failure of the anodizing or plating) or just adding a turn. Racers want the winch to hold with two turns, but even four or five turns is fine for cruisers.

CONCLUSION

We’ve had some old boats with old winches, and we’ve installed some new Dyneema lines. We’ve never had to resort to drum resurfacing to handle these new lines. Instead, we adjusted our technique. We made sure the lines had the optimum diameter, and added covers to our tails or bulked up the core as needed. The number of turns probably changed without our noticing it, since we are constantly adjusting to the conditions anyway.

If your winch drum performance is still intolerable, talk to the manufacturer. If their advice doesn’t fix things try using a line coating, and if neither of these work, try sandpaper. Unless you were prepared to sacrifice a winch drum, we’d not try anything more aggressive.

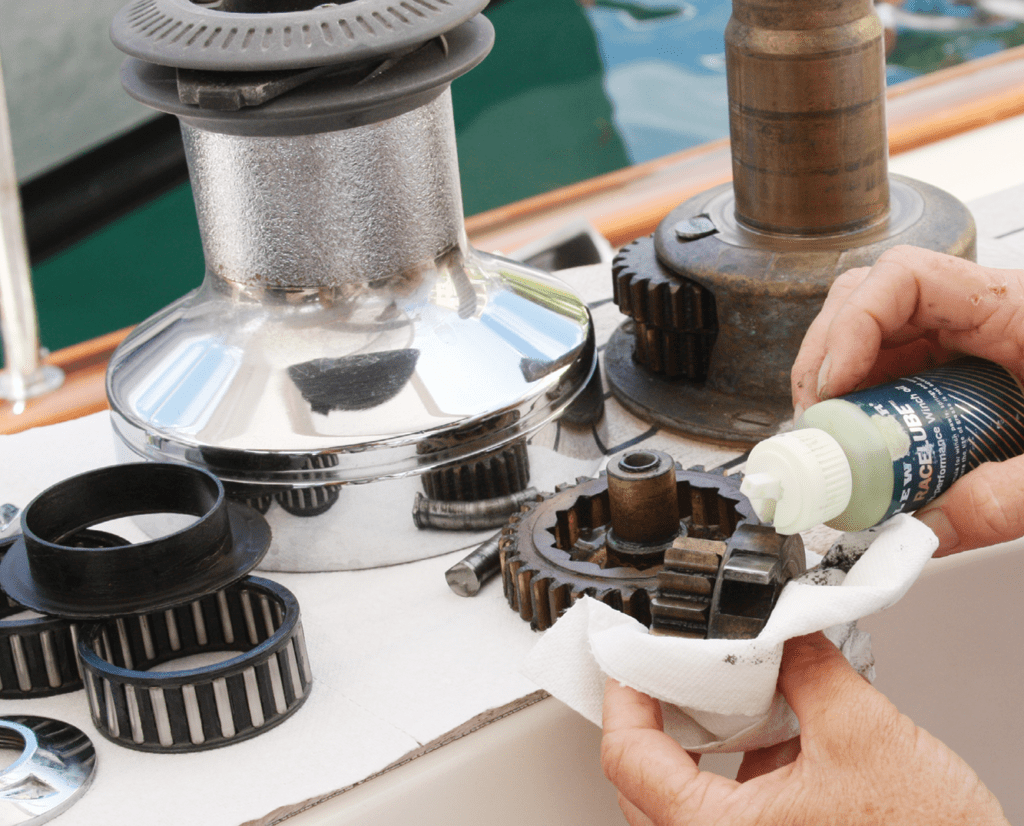

1. Be sure to have the right service kit on hand prior to disassembly. Most manufacturers have a YouTube video showing how to service their most popular models.

2. Use a light oil, not a heavy or tacky grease to lubricate winch pawls. A sticky grease can prevent the pawl from springing into place, with

disastrous consequences.

3. When it comes to greases, there are many products that will do the job just as well as brand name products (see “Budget Priced Winch Grease,” PS February 2017).

1. In 2016, Practical Sailor examined an innovative multi-geared Pontos winches, which deliver maximum power with minimum effort. The company has since been acquired by Karver (www.karver-systems.com).

2. Our 2006 winch test was the last project for legendary PS editor Dale Nouse, who died of cancer within weeks of carrying out the comprehensive comparison (see “Testing Winches with Dale,” PS November 2016).

3. What’s on the horizon? An evaluation of Selden’s new automated Sel-BUS sailhandling system that integrates sophisticated microprocessors with push-button electric-powered winches to automate sail trimming on boats like this Island Packet 439.